This is an excerpt from Your Money, Your 20s, a concise ebook on building wealth. Read the full book here.

“I’m just bad with money,” a friend said to me in 2007. At the time, I sat quietly and smiled to show my empathy. I didn’t agree but I also didn’t know how to respond. I knew she wasn’t bad with money. I just knew that she didn’t always act in ways that kept her bank balance healthy. Nearly 10 years later, I know that it’s not about being good or bad with money. Being is too fixed.

Being suggests that you’re either born with the ability or you’re not. Being underestimates an individual’s capacity to change. It also suggests the fixed mindset of the person making the statement. I can say, “I’m mixed race,” because I was born mixed race. No matter what I do, I cannot change that aspect of my identity. Being good or bad with money is not the same, but saying you’re bad is an easy get-out clause.

It’s easier to avoid the hassle of change by convincing yourself that you are or are not something. Instead, you can make that statement more open to change by saying, “I don’t always make the best decisions when it comes to my money.” There is more action in this statement and there’s more opportunity for improvement. There’s also an increased sense of responsibility - acceptance that the individual created this outcome.

Our actions determine our outcomes. Taking actions that are conducive to building wealth will help us build our wealth. So, why do many of us fail to put into action what we know? Because we fail to acknowledge and understand the role of habits in making any change.

Why Habits Are Essential To Long-Term Change

Habits allow us to live without being conscious of our every action. How often do you think about brushing your teeth? Or making a cup of coffee? Or taking a shower? For many of us these actions are automatic. They weren’t always automatic though. When we brushed our teeth for the first time, we thought about each step. Then we brushed our teeth again - remembering how we did it the first time. Before long we find ourselves brushing our teeth twice daily. Each time we brush our teeth, we think less about each step. With enough repetition it becomes second nature and we have formed a habit.

If we didn’t form habits we’d find it hard to get much else done in the day. Each time we do something for the first time our brains are fully engaged. By forming a habit, the brain can conserve its energy for tasks that require more thought and engagement. This is good news for forming habits that help you eat a balanced diet and exercise regularly. Unfortunately, the brain cannot distinguish between forming a good habit and a bad one. In its effort to conserve energy it seeks opportunities to form any habit whether good or bad.

Your rituals equal your results. - Tony Robbins

How A Habit Is Formed

Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, uses a habit loop to explain how habits are formed:

For a habit to form, you not only need the action but you also need a cue to trigger the behavior. “The cue is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical, mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.”

A cue can be something visual, a certain place, a time of day, an emotion, a sequence of thoughts or the company of particular people. You can have multiple cues which strengthen the likeliness of the routine taking place.

A reward can be a physical sensation, an emotional payoff, such as feelings of pride that accompany praise or self-congratulation.

As people strengthened their willpower muscles in one part of their lives—in the gym, or a money management program—that strength spilled over into what they ate or how hard they worked. Once willpower became stronger, it touched everything. - Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit

Improve By Just 1%

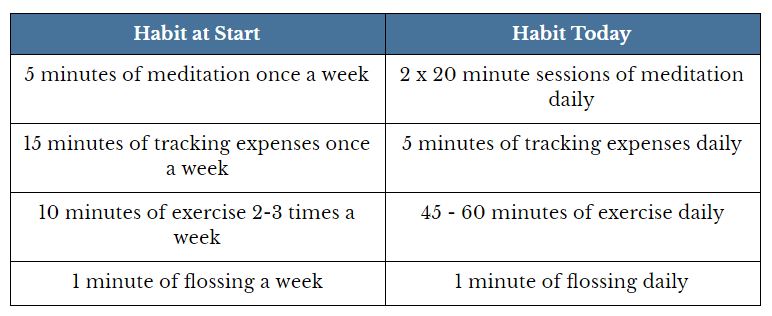

The best way to implement any change is to start small. By starting small, you’re setting yourself up to experience quick wins. Everyone wants to see immediate change, which is 100% possible if you pick a change that’s tiny. The simplest approach is to commit small amounts of time to focus on a specific activity. I started many of my habits with just a few minutes of commitment:

If measuring your habits using time doesn’t work for you, you can try reps instead:

- Write down expenses once or twice a week

- Meditate once a week or twice a month

- Exercise for variable amounts of time once or twice a week

Or you can focus on percentages:

- Save 1% of my income every month for 12 months. Increase the percentage monthly i.e. 1% in the first month, 2% in the second month, 3% in the third month and so on. In the last month, you will save 12% of your income.

- Spend 1% of each day either exercising or meditating (14 minutes)

The trick is to make the new habit so small that it’s barely noticeable. One suggestion for those who want to start a flossing habit is to start by flossing one tooth a night. It’s a small enough commitment that you’ll feel silly for not doing it, but it’s not so big that you have to overhaul your schedule.

How To Engineer Good Habits

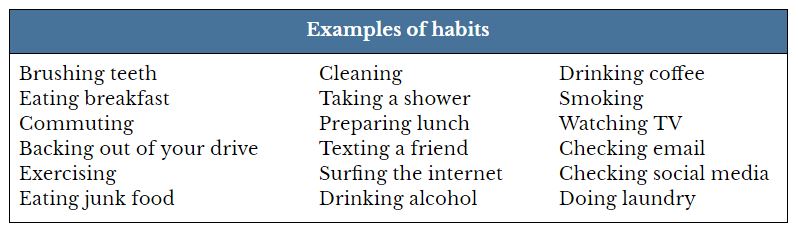

The good news with habits is that once they’re formed, they’re automatic. You no longer need to exert mental effort to get your desired outcome. The bad news is that your brain cannot distinguish between good and bad habits. You need to consciously work this out for yourself before making any lasting change. Let’s start with habits that may or may not be related to how you manage money.

Step 1: Audit your actions

Like spending, we’re often unaware of our habits until we track. If you already have an idea of what your daily habits are, make a note and then build the list of habits over a week. If you don’t know what your habits are, track your actions for a week.

Step 2: Pick one repetitive action (this is most likely a habit.) Look at your list of actions and identify any patterns. What do you do several times a day, everyday or nearly everyday? Pick one of the actions you repeat almost daily.

Step 3: Dissect that habit. Ask:

- What is the cue for this habit?

- What is the routine for this habit?

- What is the reward for this habit?

Step 4: Focus on the reward (outcome). What was the reward for this habit? This reward is the same as the outcome of taking that particular action.

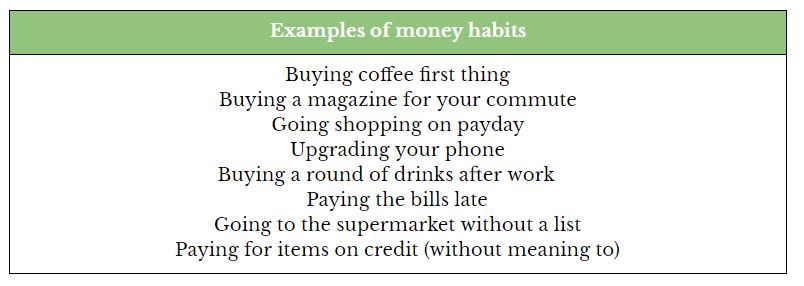

Step 5: Repeat steps 1 - 4 with one action related to money.

Look at your spending records and identify patterns.

Step 6: Ask why. With your list of habits. Ask why you have these habits. What do you gain or what do you lose? Why do you think these have stuck when others haven’t?

This is an excerpt from Your Money, Your 20s. Read the full book here.